Publication Day for My Story Collection

I’m interviewed by UK writer Matthew Kinlin about The Calendar Factory

It is the official publication day for my short story collection THE CALENDAR FACTORY published by Anxiety Press. It’s been a long time coming. So far I have not planned any book release parties or anything of the sort, but I was interviewed by Matthew Kinlin, author of The Glass Abattoir and Teenage Hallucination, and a frequent reviewer and interviewer of writers in the more macabre corners of indie lit land. We talked about crime movies, paranoia, blue collar jobs, Nabokov’s The Gift, and other topics.

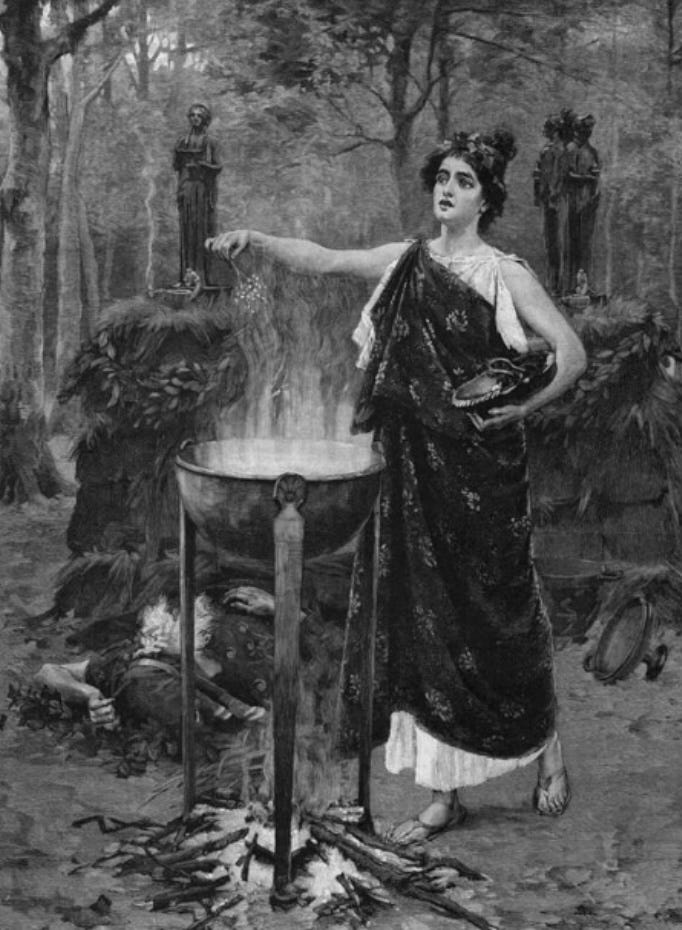

One subject we touched on was the cover art for the book, which is a painting I did based on the above illustration of Medea at her cauldron. I don’t yet know who the artist is there, but I’m trying to find out.

In the following, the bold text indicates Matthew’s questions. We conducted the interview via email. I was very grateful to MK for agreeing to read the book at short notice and do the interview.

Enjoy.

********

What’s your favourite scene from a crime novel or film?

It might be the scene in the neo-noir movie After Dark, My Sweet (1990) where Jason Patric flips out at Bruce Dern and Rachel Ward after they’ve all pulled off the risky kidnapping of the rich kid and they’re in this pressure cooker of mistrust and trying to make the next decision. They’re all conniving lowlifes but Patric reveals that he’s on another level as a dangerous psychopath ready to explode at any moment, and now he’s in charge of their operation. Patric is pretty amazing in the role. His facial stubble alone carries half the movie.

The Calendar Factory feels transitional: its pulp crime stories are mixed in with more autobiographical, essayistic pieces. The opening piece Stray Texts is a beautiful account of the changing dynamic between a father, mother and daughter, following a divorce. Can you speak about bringing in these personal elements?

I think I am in a transition artistically and the stories reflect that. It sounds lame but I think I’ve been influenced by all this current talk of autofiction and people turning to their lives as the source for their writing. For better or worse. I wrote a crime novel called Blood Trip which was of course fictional but the character’s motivations and emotions were drawn from things in my own life. It just feels better when there is some personal indwelling or connection in the writing. You’re really inhabiting the characters. I also think I was seeing certain limitations in writing crime fiction, for me at least. I still have an interest in it but I think it’s a recipe that needs tweaking, personal ingredients added.

I like how you took elements of crime fiction and found parallels in your personal life. In Don’t Say the P-Word, you describe your life at that moment as: “Midlife crisis, delusions of grandeur, thinking you’re in a Le Carré novel.” If you were to boil it down, the primary ingredient of noir fiction and film is paranoia. How was it to write so openly about mental health?

This has just been the interesting personal material for me. Writing fiction, of whatever genre, has been a process of coming to terms with the features of my own mind that get me in trouble, or take me away from rational day-to-day existence, or whatever. Putting fearful, scary thoughts down on paper feels like a strangely healthy pursuit. Please stop me before I say it’s “therapeutic” and make everybody gag. It also felt like some material that might be of interest to readers, potentially. Mental illness belongs to the individual sufferer and is a very private thing, but it also binds him or her to the rest of humanity in a deep, intricate, existential way. There’s a lot of social context and stigmatization to mental illnesses. There’s a lot that has yet to be explained. As a writer I don’t feel charged with a duty to do part of this explaining per se. But it’s something to write about. Regarding paranoia, it’s just been one of the defining modes of political life in our time, whether on the surface or underneath the radar. Paranoid people are the main characters of their own stories. Paranoia puts the individual at the center of large movements of history, significance, meaning. “It’s all about me. People are thinking about me all the time.” It’s somewhat easy to write that story, it lends itself to fiction very simply.

There’s a great line: “All a crazy person needs to do is read the news and they get ideas.” It reflects the creative aspect of paranoia. I’m thinking of science fiction writers like Philip K. Dick, or even Burroughs, that employ elements of noir and use paranoia as the entire basis for their investigation of reality. How does delusion and creativity relate?

The mind is a powerful engine of thoughts and emotions. Often really bad ones. I’m no psychological self-help guru. But I think it has something to do with tempering the imagination and using it to produce something usually external to yourself. “Creativity” is almost a word with too many positive connotations when you compare it with a word as freighted with negative connotations as “delusion.” Art, it seems to me, is about making something beyond all these connotations. I have a soft spot or a love for art which retains some of this fear or dread.

In Continuity Girl, you list continuity errors in films, including Dorothy’s hair changing length throughout The Wizard of Oz. Can you name three films you would associate with The Calendar Factory?

I’m not as up on films as I used to be. I worked in a video store as a teenager. But I can’t recall every movie I’ve seen. I suppose the movie River’s Edge might be a kind of touchstone because it seemed like a somewhat rural setting for a dark crime drama. All those eccentric scummy characters. I love that movie, so much. When you mention River’s Edge it feels like just a hop, skip, and a jump to Blue Velvet and David Lynch. As a teenager I was totally taken away on a fantasy ride by Twin Peaks when it aired on TV. That whole notion of extremely dark, dreamy mystery set in small town America spoke to me and left an indelible impression. As for a third movie, there is a story in my collection which is sort of fan fiction about a character from Raiders of the Lost Ark which was my favorite movie as a child. His name is Belloq in the movie and he was this fascinating French collaborator villain who in my estimation was just using the Nazis to further his own intellectual goals and obsession with history and time. I was just having fun writing about him.

You speak in a candid and refreshing way about work, from the gruelling dairy farms of upstate New York to the factory of the title story, where: “More likely he’d just go work in the calendar factory, gluing cardboard corners forever.” What is your experience of working life?

I just barely got a Bachelor’s degree after many failed attempts, so let’s just say I was never professional white collarmaterial. I have worked in a calendar factory, and then in a dairy processing plant as a quality control lab tech, and also on my uncle’s dairy farm milking cows when it was going. I worked for many years setting up conferences and weddings in a large four-star hotel not far from where I lived at the time. Which just means humping a lot of tables and chairs all over and installing dance floors and risers. Upstate New York doesn’t have plenty of job opportunities like a city would, presumably. I worked as a freelance newspaper reporter for about eight years which was a little more mentally stimulating I suppose.

You mention Nabokov’s The Gift as your favourite novel, which I have never read. What does this book mean to you?

It’s an utterly beautiful novel about a young Russian emigre poet living in Berlin who has these intriguing encounters with fate and love. Its poetic language is marvellous. Some have called it Nabokov’s farewell to Russian literature in a sense because it was the last novel he wrote in Russian and it has many Russian themes and points of contact with older Russian writers. I recommend this book to you wholeheartedly, and I should make time to reread it myself.

You find deadpan humour in intrusive thoughts and magical thinking, in lines such as: “Kissing a light socket seemed like a painful and grotesque way to kill yourself, my therapist said.” How does humour relate to these moments?

That’s just a transcription of what was really said. I’ve had fascinating relationships with therapists and sometimes you have this itch to make your therapist laugh or show signs of life, and it goes back and forth. I’m sure there’s a psychological term for it. But no, I find that injecting mordant humor is a way of introducing a crucial degree of insulation to painful subjects. One writer I admire who does something kind of similar to this is Audrey Szasz. I’m not sure if I 100% love her writing just yet, but she writes these horrific works of fiction, extremely dark, graphic, unsettling, but there are these flashes of wit that let you as the reader reorient yourself just a tad, before being thrown off base again by the terror. I like that. It’s a unique mix of tones. We were talking about Twin Peaks up above. That show, and arguably one of David Lynch’s characteristics as an artist, is this unsettling mixture of tonal qualities, bizarre comedy and pathos and fear. I don’t know quite what it’s accomplishing aesthetically but it’s like a signature, a style. The laughter in the dark. I can’t do it as well as any of these, but it’s on my mind, I suppose.

The artwork for the collection is really striking. How did this come to the book?

I’ve been painting some lately. I paint very slowly. I’ll start a painting and finish it years later. The cover art for the book is a painting called “Medea Plays Tetris with AR-15 Parts.” I have this idea that, if I am a painter, I’m trying to work in a classical mode that is tinged with an updated hallucinatory quality. I really love the extremely skilled painter Robert Williams who has his own visual vocabulary based on LSD and pop culture and that kind of thing. But I’m a very naive, rough painter. So for me it’s old themes with some new brain damage and horror laced in. Medea killed her children but living in America, there have been an untold number of mass shootings. It keeps happening. I thought how would she kill her children today, in 21st century America? The Tetris thing, I don’t know, it had something to do with needing a background, a screen that would suggest an obsessional technological game. What does it have to do with the book? I’m not sure. It just felt like a striking, violent image that had neoclassical possibly literary resonances. Also, I have nothing against book covers with AI art I guess, I just don’t want them on my own books. Art costs money, I get it, publishers can’t swing it. But if I could provide my own cover art it would be free, right?

Given the title of The Calendar Factory, if it had to be one month forever, which month would you choose?

I think if it could be October forever, in the place where I live, with the foliage and the temperatures, it would be heaven. But that would be an absurdity because autumn is about elemental change and transitoriness and would certainly lose that profundity, that passage, that process, if it were eternal.

Lastly, if we meet in another life as spies, what is our codeword?

Those evocative codewords. There’s a playfulness to that aspect of espionage, isn’t there? Like the true-life Balkan spy that Ian Fleming based James Bond 007 on was reputed to have the codename TRICYCLE, apparently since he was always having threesomes. If we were spies, Matt, I’d send you the word SNEGOPA to tell you things were all clear. It means “snowfall” in Russian, I believe. If I say ISKRA (“spark”) that means you’ve been betrayed, and to trust no one.

*******

Utopian book-lovers will be troubled by the fact that currently The Calendar Factory is only obtainable via the Amazon dreadnought where we are but mere stowaways. But I will be ordering copies of my own for sale on my own terms shortly. People interested in that option living in the USA can contact me by leaving a comment below or getting me on Twitterx. The book is $15.00. It’s a collection of sixteen stories that were published at venues such as Punk Noir, Misery Tourism, Bruiser, Anti-Heroin Chic, Bureau of Complaint, Pulp Modern, and other publications. Try to support indie literature where and when you can.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DFLZFL43?linkCode=ssc&tag=onamzathinsli-20&creativeASIN=B0DFLZFL43&asc_item-id=amzn1.ideas.1T5FJB96438FO&ref_=aip_sf_list_spv_ofs_mixed_m_asin