PORCUPINES IN LOVE

You ask for help. You ask some male novelists to come together and help you lift this memory, to get a grip. Faulkner and Hardy and especially D.H. Lawrence to assist you as you try to carry the memory of moving the heavy cider press from the front porch of Tony Larry’s broken-down farmhouse to the side cellar door. The memory features you, Tony Larry, and his boyfriend Brian wrestling with the contraption of metal and wood, to put it into place. You helped the two of them move the cider press from the cluttered front porch to the stone plinth by the crumbling cellar stairs, splattered with ancient moss, conveniently located by the boxes of apples in the cellar, the waxy cardboard boxes of gleaned apples from the old farmer’s tree nearby. A single apple tree gave fifteen boxes of small, tough green apples. Tony Larry marveled at this to you on this chilly autumn day, not to Brian who already knew, but to you, sharing wonders with the outsider, now so outside of the life you once knew. When Brian and Tony Larry and you carried the cider press, you deliberately—but you don’t know why—didn’t carry it fully, didn’t exert yourself. Something passive aggressive about your lack of effort, that they might notice, might not, because you were three lifters and the responsibility could be put on any one of you. You were off the farm, not strong as they were, they had strength together. You were excluded from paradise. It was chilly but Tony Larry was in a tank-top and once the press was assembled, glass jars in place, he started feeding the apples into the hopper and twisting the press-wheel. You snuck an iPhone snap of Tony Larry’s long body, bending, and Brian watched you take the picture, and you felt a thought open up in Brian, a private objection. You don’t spell “objection” with the K as you often do, to indicate the strangeness, the Unfamiliarity, the German-ness of objekts (you don’t know enough German to say why, only to write it so in private diaries). But Brian’s negative feelings took shape, in your telepathic space, a void torn open. You could read minds as jealous people know they can do, or at least, delude themselves so. The scientific truth of telepathy was unquestioned to you as you “dodged your salts” that autumn day: no sike meds. The piles of ugly apples would never have found a place at the supermarket. They were filched apples. Tony Larry and Brian were renegades, cooperating to steal the apples, another exclusion zone you were put into. The photo of Tony Larry, before you deleted it, featured his arms, his triceps pendulous—may you not write something stereotypically homoerotic, or try not to—but his muscles led you to feel it had been okay to go slack while lifting the awkward, heavy contraption. You were submissive whereas when you’d helped Tony Larry build the goat fences months or years earlier, whatever interceding chronology was likely given Aubrey’s time with you and her departure. Brian hadn’t been there then, but he was here now, playing an role, deferent, subservient, handing you a jar of dusky apple cider, saying, “Want some?” You tasted it and it was delicious, sweet nectar.

///

The distance in time was so great from memories of love, so that equally distant from your thoughts, and difficult to retrieve, were the reminiscences of that feeling, of “I’ve never been in love before” after a disillusioning catastrophe, that and that “I don’t believe in love.” Even the cynicism is a weathered artifact buried under layers of dirt and gravel. “I don’t believe in love” is a statement dependent upon the fresh happenstance of love’s turmoil. When it has been years, you don’t think one way or the other, believing in love, or indeed not believing in love, both are like programs conveying information that have been dialed down in volume on some emotional broadcasting equipment deep inside. (Welcome back, machine analogies.)

Questions of love, love’s philosophy, are stale, impossible to entertain when it has been so long since you’ve been trapped within the ambient gel of those sentiments, with no one to clearly project potent fantasies onto, nobody to serve as fuel for—onto, for, some preposition indicating a romantic enmeshment or encounter. When all this apparatus is dormant, defunct, the mind cannot investigate the breakages, even in memory.

Dreams of doggystyle sex: you would think would be pleasant, but in them, in the script of their narrative mesh, were retained the facelessness of your partner, the nullifying degradation perhaps. Whereas you want to see and hear the voice, synchronized by the dream editor’s soundboard. You still hear the voice, but it isn’t part of a complement of sensations, seeing the mouth move in sync with the voice crying out in pleasure or pain. Which sensory incoherence renders it all pain: your ex-wife Natasha is uncomfortable and angry in your sex dreams. A nightmare of some confusing kind, at least.

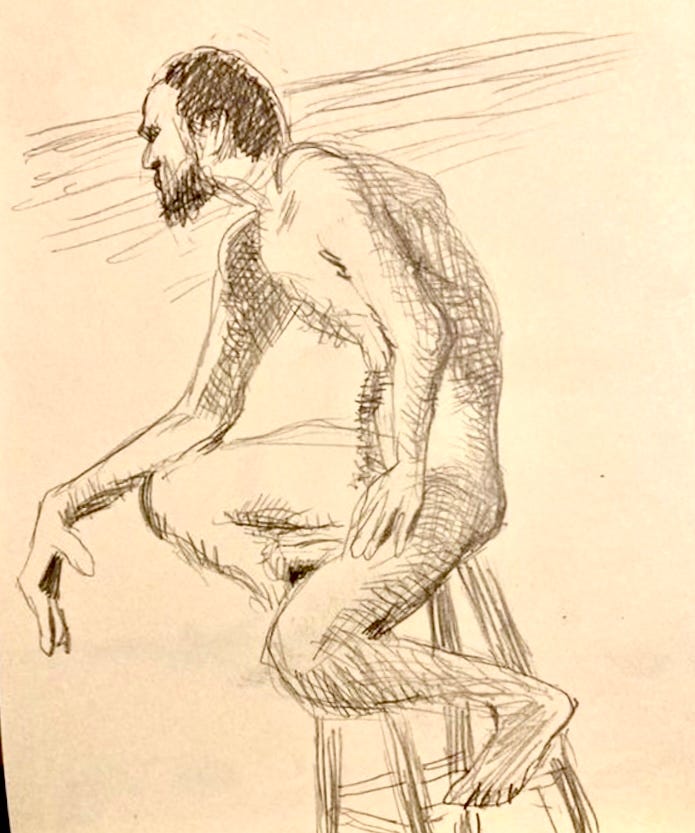

It was within the atmosphere of misrecognition, or forgetfulness of love, that Tony Larry surprised you and confused you. The emergence of the vision of another interrupted of the conscious drone of thoughts, when all comparable models that might have served as guides or proofs had been lost to time. Tony Larry’s relationship with Brian gave it an edge which made it real for you. Another way of saying this is that the lonely man doesn’t know how to think about love; to the contrary, he is more ignorant than the youngster who has not yet crossed paths with love, and experience is no prophylactic, at least to the emergent feelings of love. What he does with the feeling, how he tends to it, encourages it mercifully, or strangles the life out of it where he finds it, is his business from that moment forward according to his training and his temperament. He won’t be properly prepared to deal with it if he’s been out of practice, though. This is how you found yourself with Tony Larry. It wouldn’t make sense to list off the farmer’s physical traits, his appearance, his manner when you are near. It is not a recognizably physical attraction—you swear it—the blond hair and strong arms from lifting the arrayed objekts of the goat farm are as irrelevant as his gender seemed to be, to the inner cupid’s intelligence and aim releasing darts in all directions when you were around, and without armor as Aubrey had left you.

There are a million parts of you, according to some arcane division, as many parts as there are discrete moods in a day, between waking in the morning to a daily metempsychosis, and going to the oblivion of sleep at night (to say nothing of the efflorescence of the restless dream-selves, seeking and finding sexual objekts, partners, bodies, in the dark stacks of your mental warehouse). Only a handful of these parts of your self have the articulacy to know what is going on, to be stimulated and summoned into a love movement. These articulated parts are mostly beyond the reach of your conscious thought, of your decision’s radius. Articulate yet mute, to you. But articulate in what way? In that they know how to register the texture of dream life. These elements of erotic dreams are objekts passing in front of you, just as solid and real and external to your consciousness as any physical, mental, or digital objekts can be. And your misspelling of the word is tactical in nature, just as your misspelling of sike-ological is tactical, a defamiliarization and a reclaiming, a revelation of the ropes and pulleys visible on an inner soundstage which would otherwise escape notice.

///

Dodging your salts, no sike meds: You have a home in the countryside outside the city of fog, but your vicarious homelessness is experienced through your teeth. Pain-plays pain-films pain-dreams. What would have happened if you had been unhoused and neglectful of your health, but it’s really happening. Your brain is a cranial abscess. You were warned that you could lose the sexual module if you weren’t careful. The risk is that it could become detached from the brain and float into a dangerous area in the eyeball. It had happened on a number of occasions, something about the binding sutures not being strong enough. The whispered about, oh-so-feared glitch of false notification in your visual field. Blue dot that wouldn’t go away when you clicked on it. Horror symptom indicating something went frightfully wrong deep in the recesses of your mind media.

It is borne out by the algorithm, you think you can say.

Controversial sex sike-ologist Wilhelm Reich was circumcised on June 8, 1895. Cross-indexed with Bjork’s vocal cord surgery, the singer had a polyp removed in 2012. Use these two points in time to extrapolate, triangulate a third, a cutting away of something unwanted in your body. Or my body. It doesn’t matter, the third point of the triangle will float between you.

Aubrey is gone. You’re a different person now that you’ve been talking to the cops. Other antechambers of personality have opened up. “I’ve trained myself for on-the-job sexual compliance,” you say to the FBI microphones concealed in your car as you run errands around the city of fog. “I’m a self-starter.” You technically meet the standards of a certain personal working definition of bisexuality. Navigating the Scylla and Charybdis of gay dating when you’re not even gay. But then bang, your subconscious springs an intricate/dramatic/touching gay dream on you when you’re not expecting it. A vivid multilevel ant farm narrative of a gay story involving you and Tony Larry. It’s not sexual, more romantic. Being very sexually attracted to women over decades of libidinal experience, loving looking at nude women and letting imagination and fantasy play with their bodies — but fully cognizant of forming strong crushes on men, empathetic desires for friendships and relationships with members of the same sex. Different valences of attraction hold sway, with one side of the formula not recognized as such until later in life. You wanted TL to be photographed with you at the antique store on Hospital Street, miming sike-oanalysis: Tony Larry on the luxurious couch, chaise lounge, fainting chair, whatever, you seated in the analyst’s position behind Tony Larry’s head in a metal folding chair with your legs crossed as you never do in waking hetero life as it is a gesture toward femininity, with your spectacles on the end of your nose and a pad and pen in his hands. TL’s gesturing and talking and you are wincing slightly, the wince of analysis. Or else you are switched places, you’re on the couch TL in the chair. The antique shop owners indulged you two in this comical tableau. Brian wasn’t there so somebody else in the fantasy took the photos.

At the other end of Hospital Street, once you left Tony Larry, you went to Stewart’s for garlic pizza. You got coffee and all the wooden stirring sticks were broken, every one, bent like a hockey stick. The creature that followed the checkout girl to the cash register, she went behind, she handed her credit card to him, he put it in the reader, swiped angry, they both waited for it to approve, then it did, and he handed the card back to her and took his iced coffee and asked her when she got off work. “11:30,” she said. It’s a life and no mistaking.

You went to a local art show opening yesterday. Tony Larry, the hipster farmer, handyman, was there drinking a fancy coffee from faraway lands. Brian was with him drinking some outrageous martini and playing parlor games, word associations. Later once you got home, you’re running back every social cue overlooked until it was too late — a hypochondria of subtle social maladjustment. Not that the stakes are high or anything. Just privately missed targets of savoir faire. You went home and fell into a thousand pieces. It means so much to the cave dweller who couldn’t hunt or gather anything except awkward handshakes and hors d’oeuvres and small talk. He doesn’t know you’re friends (you’re not, it’s flirtation). He doesn’t know you kill (you don’t, that’s just fiction). She doesn’t know you will (you won’t, that’s just friction). They don’t know you still (you whisper malediction).