Picture A '90s 'Outsiders' On Meth

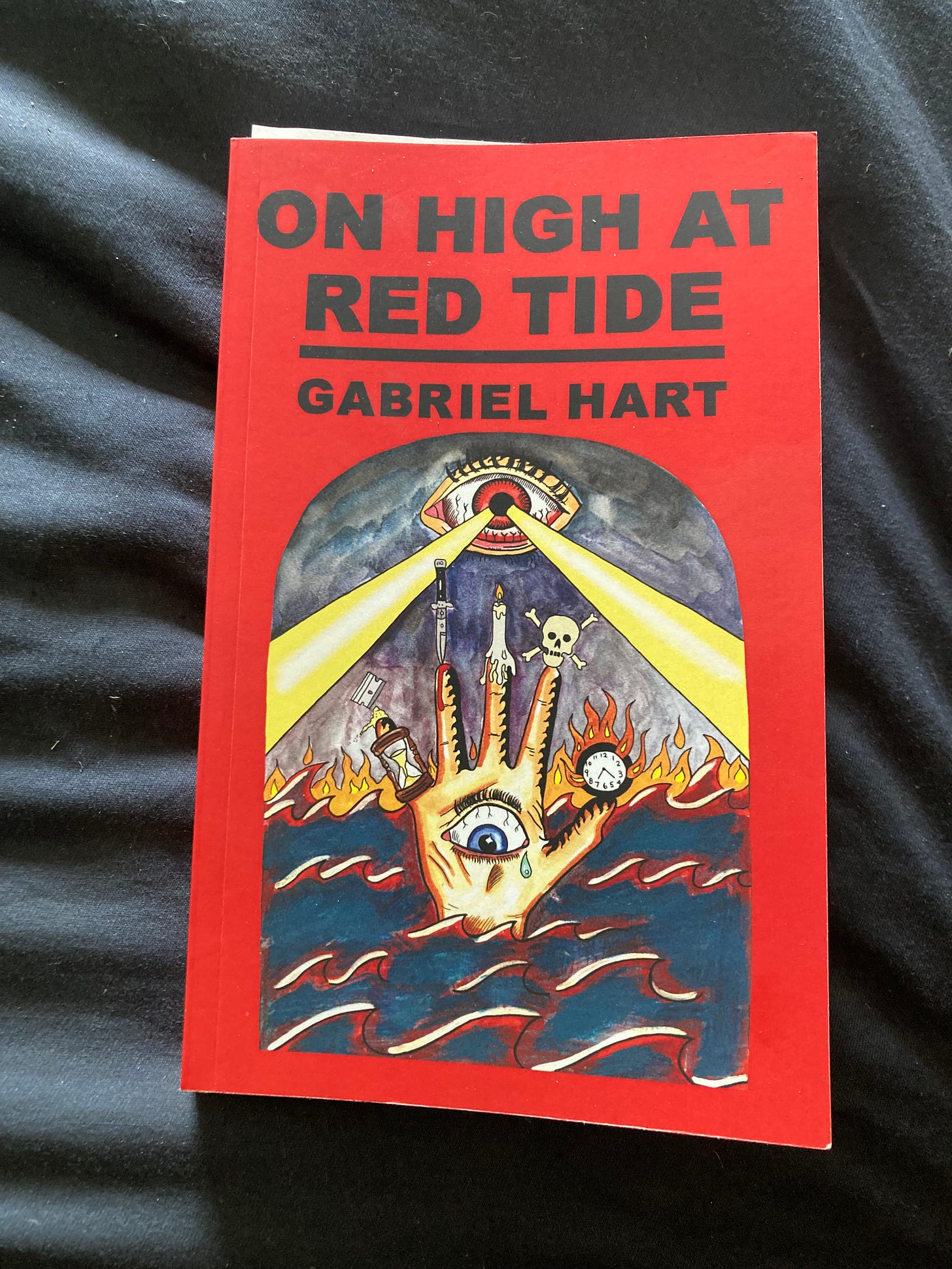

SoCal punk teenagers get spun in Gabriel Hart's new novel On High at Red Tide

Gabriel Hart, the writer and musician from Morongo Valley, CA talked with me via a jerry-rigged Google Docs interviewing process about his 2024 novel On High at Red Tide published by Pig Roast Publishing. Once I could focus, I read the novel in a matter of two or three days; I reported on Instagram that I found the book to have “a truckload of balls and energy.” I stand by that estimation. The book was so much fun and yet so dark and laced through with painful regret over its characters’ wasted youth and potential. The story involves a gang of punk kids from Laguna Beach, CA who call themselves “The Vigil.” Pretty soon they get involved with dealing drugs, methamphetamine, specifically, to their wastoid beach town’s denizens. There’s no way out, addiction and psychosis develop, and they have to rely on each other for protection and a sense of belonging as drug rivals and cops patrol the streets looking for retribution. Repercussions can only be dodged for so long…

Jesse Hilson: First of all, I really liked the book and found it took off for me after a short period of getting used to the characters and the world (I also was dealing with some life and work distractions so I didn’t jump on the book right away). Once I was there, it was very easy to get pulled back into the book after I set it down. As I said elsewhere, the main aspect of the book that is most notable for me is the speed, the pace, the propulsive quality of the book that takes over for the first 2/3rds of the book. I’m curious where that came in because I know you worked hard on the book and it went through several drafts including a much longer draft of 450 pages. Was this speedy quality there from the get go or did it come in through editing later?

Gabriel Hart: Speed is fast. Since the book is largely about meth, I wanted to challenge myself to see if I could replicate the experience for the reader of being on that drug. Since I have never been satisfied with any depictions of meth in literature or film, I aimed to animate the drug’s inherent psychosis by trying to induce insanity in the reader, as if the text itself was accelerating out of control. When you’re on that drug, you have a hundred internal narratives happening all at once––all unhinged conspiracy––yet you’re only able to communicate a fraction of all of this though your mouth in very broken language, so I wanted to see if the novel could pull this off while retaining a very tight plot.

The reason why the first 2/3rds move faster than the last 3rd is because that’s where the meth use stops and the slower churning remorse begins. From that point it all becomes painfully logical and suffocating with the gang’s regret that they’ve killed somebody.

The original 450-page version that my agent tried to sell was really overinflated and not what I had set out to write. When you pull from real life, you tend to hold on to sentimental bullshit that has nothing to do with the story you’re trying to tell, and unfortunately, I feel he had plucked me and the manuscript too early. Working with Elle Nash, who helped with developmental edits, then later with Lisa Carver, who really dug in there with me to get that language fine tuned, were both what the book really needed, not an agent. I was able to cut the book right in half, no bullshit.

One thing I felt about On High at Red Tide that I didn’t get into in my Goodreads review was that it felt to me like a very pleasing blend of different flavors: a rip-roaring story; crackling prose describing characters’ inner states; a drug novel that had elements of suspense, humor, horror; and a significant amount of brain-teasing mystery/puzzle box action toward the end. And add to this the emotional undertow of the ending. I was especially intrigued by the mystery aspects. I don’t want to spoil anything because people should read the book for themselves. I said it elsewhere but this book had me questioning all kinds of things after I’d read it. I almost lurched upright in bed asking myself “Ok, did what I think happened there really happen? Did Gabriel strategically fuck with my head over some clues?” Was that aspect in the original blueprint of the novel, to the extent you can talk about it here?

The original 450-page manuscript was honestly very square, very linear; I was pulling too much from real life events and it didn’t translate to the kind of fiction I wanted to write. The internal lunacy I was feeling from recalling these events wasn’t actually making it on the page. In my head I thought I was writing a cold, detached journalistic style like Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, but it wasn’t ending up like that. The mysterious murder was always there; I just had to remove it from its “murder-mystery” trappings. So once I got it back from the agent, I felt more comfortable getting weirder with it. I leaned further into the cognitive dissonance of murder as a crime of righteous passion and intersected it with the psychosis of drugs, while leaving intentional loose ends so the reader might feel their own conspiracies bubbling from their own unique perception of the book.

Was there a real Vigil? I hadn’t heard this part of the background but I’m assuming this is the real life story you’re alluding to.

I don’t mind you asking but I also made a solemn swear to myself not to comment too deep on that anymore. I ended up fictionalizing the novel further in order to further protect identities I wasn’t being mindful of in my striving for authenticity. Even when the novel came out, I dealt with some serious fallout from a very close friend of mine who read it, and it made for some very emotional consequences that took a lot to come back from. We are all just really sensitive about that time in our lives. But I also maintain that compared to the original manuscript, as a whole narrative arc, I did the work of fiction independent of anything that actually happened.

The novel is more influenced by a nightmare I had in 2014 that alluded to a worst case scenario of our past, so essentially the story is me trying to reverse-engineer that nightmare, and maybe figure out why it chose my subconscious, and what it says about some guilt and trauma we may carry. Beyond the novel, there’s a whole paper trail of stories I’ve written to hold that time accountable but I’ve also chosen the form of fiction to burn the trail of facts behind me as I go.

Ok, that’s fair enough. But zooming out, outside of these specific details, you were writing about Southern California in the 1990s, that’s a true setting for you, correct? I really appreciated the texture and the historical accuracy, if we want to put it in those terms. Regardless of treading on the true stories of friends, it does a marvelous job of putting the reader into that locale and making it all vivid.

Correct. I wanted to capture south Orange County in its last gasp of seediness before it all changed into the sprawling fortress of wealth it is now. A large part of Laguna Beach was literally built with drug money––a lot of those mansions in the hills belonged to associates of the Brotherhood of Love, the Hippie Mafia, who synthesized Orange Sunshine LSD hellbent on turning the world on, before turning to harder stuff and international drug smuggling. So there is a lot of cocaine in those hills as well.

Because of the Orange Sunshine acid and the Brotherhood, The Manson Family used to visit Laguna. Decades later, when I was growing up there, even before I knew who Manson was, there were similar creeps like that hanging around, so by the time of the late 80s/90s resurgence of Manson’s popularity, he was an instantly recognizable, even comfortable image and concept to me and my friends––the kind of guy who could have been pals with my parents at one time, unbeknownst to what the future held.

So essentially, me and my friends were mimicking the behavior of that kind of localized boomer generation, sculpted by their stories that would trickle down to us. But what made our upbringing unique was seeking, or maybe surrendering to, the undertow of that early 90s methamphetamine epidemic in the spirit of being crazier than our parents, to set us apart further.

Another feature of the novel I enjoyed was the writing itself, which feels like it pushes the book past just being a mere chronicle, or perhaps even just a kind of featureless, bland “screenplay novel” made up of 90% dialogue. There are nice touches, such as the drug dealers looking at junior high school kids as potential meth customers, specifically D&D nerds as gaining “experience points.” The out-of-touch alcoholic Mom, who was a harrowing character of neglect, sees her TV blasting the Menendez trial as an “ageless babysitter.” So I’m saying there was a poetic finish to a great deal of the language along the way, and this was balanced well with other things like the plot construction and the pacing. A drug novel sort of cries out for poetic descriptions of interior mental states that have to be a) interesting to read, b) fresh, and c) accurate to the drug experience. Did that prose style come naturally when writing the novel? Or was this sort of substance injected into the bloodstream of the novel in later drafts?

When my agent returned the manuscript to me after trying to sell it to 23 of the biggest publishers out there, he said, “You’re obviously free to do whatever you want with it now,” and I took that very literally, like a dare, and I felt a great freedom from that point forward to make it the strange book it was always meant to be. So instead of making something marketable for the big game he was talking, I went the other direction; a darker, psychedelic approach that offered more riddles than answers, which is more authentic to that drug and that sort of punk rock lifestyle. The manuscript became a total blast to write from that point forward after Elle’s developmental feedback, where I knew exactly what I had to do. I think subconsciously I returned to a lot of authors I was reading as a kid like Hubert Selby Jr. and James Ellroy who really shaped me, and retapped myself into that manic energy in the present.

Initially, I rolled my eyes when early readers commented it was “lyrical” because I was consciously trying to write a punk rock novel that was not musical. But I did notice myself rhyming a lot in the prose so I just said ‘fuck it’ and leaned into it during the final edit, since meth also convinces you you’re very “clever,” like everything you’re doing is predestined or poetic when it’s all just psychobabble.

I’m picturing the end of Wild at Heart with Sheryl Lee hovering above Nicholas Cage as the Good Witch saying in her high-pitched voice: Don’t run away from your lyricism, Gabe.

It’s annoying because I’m a very reluctant rhyming poet too. I’ve trying to keep poetry separate from my songwriting habits, but I’m also trying to relax about resisting that now too, because I think there is a different value there, and almost more of a challenge to write a great piece of poetry in that form, so I am trying to carve that out with more confidence. My friend Boris Dralyuk is a prime example of a modern rhyming poet who absolutely kills it, definitely someone to strive towards.

OK. Lightning round! Forgive the superficiality of some of these types of questions. Quickly, for a contemporary writer, what’s the best ratio of IRL interactions (readings, in print publications) to online (social media, cyberwriter networking, Zoom calls, etc)? 50/50? 60/40?

Regardless of any of those ratios, I think it’s most important that a writer places more value on being a human being first and foremost, not weighing our place in the world on our creative output. We often forget to be a present friend, or even a caring stranger, to others in our direct proximity both online and in real life. I know a number of writers who completely shut themselves out and avoid interacting with the world they’re trying to write about, and their work suffers horribly from it, though I think someone like James Nulick would be an exception here. He’s on another level where he's actually earned his isolation.

Location is also a huge factor in this. I live in the desert, and while I have a small community here, the isolation remains an insidious presence that’s hard to outwit, and it can really eat you away if you’re predisposed to negativity and depression, so that’s a big reason why I’m often reaching out to people, reminding them that I’m here and that I see them too. The whole “signaling through the flames” thing.

Now that I’m really thinking about it, we have likely entered the Age of Isolation, ushered in with the pandemic, and the popularity of autofiction is probably reflecting that. It’s easy to see it as a selfish, overindulgent form, but I think it’s also important to have it be a time-capsule of where we are/were for future generations. I just hope we’ll eventually find our way out of it.

I’m incredibly isolated myself, in a “sub-rural area” and defiant about it, and I want to yell out to the world that I love it, even though it means no one in NYC or LA will ever know who I am. I’m part of a local writing community, which is good. Online is full of mirages and trick mirrors. Another lightning round question and then we’ll get back to serious business: one way I know your work, and it was one of the earliest, was through your band Jail Weddings’ YouTube videos. You keep your foot in the door making music. I have been dying to ask you if you have heard of a band named Cindy Lee, from Toronto. I ask because I wonder what you would make of their sound, their girl-group atmospherics. I heard them on satellite radio while driving home from work and thought of your music.

When I was a teenager into my 30s, I had a love of playing/writing music, then in my 40s I had a hatred of it, now in my late 40s I have a healthy, balanced love/hate relationship with it. I have a new group called HOTEL MERCY, though you might never hear or see us ‘cause we are just here in the desert keeping a lower profile.

I wish I would have committed to writing prose at an earlier age. I got to see the country a dozen times and then Europe, and made some of the best friends ever but in retrospect a lot of it was a waste of time, especially since our culture barely supports it now. So much of being involved with music is just waiting for something to happen. When you’re writing, it’s happening.

I just listened to Cindy Lee. They’re good, but maybe too classic rock for me. This is going to sound pretentious, and maybe we were, but in contrast, Jail Weddings was more of a postmodern art project that had more to do with Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty than 60s music. We were trying to help bury rock n’ roll by being very garish, ridiculous, and confrontational but we just happened to make good records too.

My favorite Jail Weddings record is probably Love is Lawless. Good lyrics, maybe you’re over it, but I like “I was just, eavesdropping, so I don’t have to be alone.” I’d recommend the band to any of my subscribers and readers here at Chlorophyll & Hemoglobin. And, it goes without saying, your writing including On High at Red Tide. In the past you and I have often talked about something about the writing we’re trying to push forward, how it is an attempt to diverge from styles and genres and trends. It seems like where the book landed, with Pig Roast Publishing out of Providence RI, was a step into this realm of “the unique underground book.” You could have tried to publish with, say, an indie crime publisher like maybe Rock and a Hard Place, or Shotgun Honey, or other venues, and it would have worked also, but you went with Jeff Schneider at Pig Roast. It seems like you were in pursuit of some other literary strain that had a certain edge or pedigree, even beyond indie crime as you often see it. Can you talk about that? Do I have it all wrong?

No, you’re right. Since my intersection of reading tends towards crime/noir and more challenging transgressive material, I wanted to write the kind of book I wanted to read. I’m often fed up with a certain kind of contemporary crime fiction where the plots are too convenient and seem like pandering bullhorns for the author’s personal politics rather than work that is legitimately mind-altering in the way that earlier crime fiction first attracted me to the genre. There is also a certain kind of politically-correct contemporary crime-fiction that also has enormous body counts, or grotesquely gruesome ends for “bad guys” who morally “had it coming,” and I’m also getting burnt out on this, especially while we are witnessing the holocaust in Gaza and the sick narratives we were fed to justify this massive slaughter. Incidentally, I find it odd that literally no one in the crime-fiction community is speaking out against the holocaust when so many of them claim to be so morally sound.

With On High at Red Tide, I wanted to meditate on the concept of murder and reconsider its origins of an actual sin, so there’s that refrain throughout the book: You can’t teach someone a lesson when they’re dead.

You mentioned Rock and A Hard Place and Shotgun Honey, and the irony here is that I’m frequently published by them, but I think the fact that they’re among the most discerning in the genre is the same reason why I never considered taking this novel to them, because I felt they might have seen it as problematic: the main antagonist being a gay man, the story’s unsettling sympathy for him beyond the grave even though he may have molested a teenager, children doing morally abhorrent things while sort of glorifying drug use, combined with all the novel’s experimental prose and poetic liberties; I just felt the novel wasn’t for them or their audience and I was hesitant to risk it being misunderstood, even though they continue being supportive of my work and me with theirs.

I approached Jeff at Pig Roast and luckily he took it almost immediately. He and I have a similar trajectory as musicians who are prioritizing writing now, so I felt a certain comfort there being part of a more punk rock press. Pig Roast seems more concerned with creating a unique body of work in their catalog rather than following more lucrative trends, and while there’s a sense of immediacy with them, they put a lot of care into the editing process, cover art, and then the spirit of actually getting in the van or on the plane traveling to other cities to do readings, so this feels like an extension of what we used to do with our bands, almost like we already had a secret language and understanding when we started working together.

That’s great. I can feel that energy at Pig Roast Publishing. I went to one of their readings in NYC in summer 2024, and I regret that I didn’t catch your tour when you came out to the East Coast. I wanted to ask more about editing since there is a somewhat lively debate happening on Substack (or maybe just a series of impassioned arguments) over why people get so stuck on editing, and whether editing serves a kind of gate-keeping function for writers. It usually costs a lot of money to hire an editor or get an institution to accept your writing and have an editor look at it. I know those two ladies you mentioned have very big reputations. I’m in the process of reading Lisa Carver’s The Pahrump Report, it’s wild. And I’ve read Elle Nash’s Nudes: also great. You are studying to get a degree in Editing from the University of California currently, is that correct? What would you say to people who hate editors and think they’re meddling busybodies? I just hasten to add that whatever editors made this novel of yours so lean and mean did a great job.

I wasn’t aware people were debating the concept of editing so I automatically think that’s absurd, self-sabotaging, and sad. When there’s not another pair of eyes on your work before it’s published, it can tend to have an alienating effect, like something so personal and indulgent, the writer can forget what is actually important, or what the story is they’re trying to tell.

A large reason why I am doing Beyond the Last Estate as a print-only magazine is to hold myself more accountable as an editor. It’s so easy to publish something online, and it’s instantly gratifying, but it can lose the gravity of detail. I’ve stopped reading certain online journals because of this lack of care. I prefer interactive collaboration. I’ve been appalled by some of my stuff that’s been published online where the “editors” didn’t lay a finger on it, just copy/pasted, and I cringe looking back on that work. Once something is in print, I know the errors are much more obvious, so it’s higher stakes. It’s a lot of work to stare at every single line and scrutinize every single word but far more gratifying than online for me. Our readers and contributors have expressed this as well.

While I’m halfway through getting my editing certificate at UC Berkeley, I’m not sure if I am going to continue. I work two demanding jobs, a radio journalist and liquor store manager, and drove myself insane this past spring trying to juggle it all. I wish there was a way academia and the working class could harmonize. Even though I passed the final, I don’t know if I can put myself through that again. It’s either my mortgage or an editing certificate, sadly. I was only able to afford the course because I got injured at my pre-pandemic employer, acquired a lawyer, and was awarded a chunk of money for “vocational rehabilitation.” So I had to disable myself to even go back to school, which is likely the wrong approach.

Being on Substack I have to confess to a degree of thoughtless “fire-and-forget” self-publishing although I do worry about what I’m putting out there from an editing POV. I think when it comes to books there should be more of a screening process and more of a deliberate remove. I recently looked up at my wall and revisited a sheet of paper long forgotten which was my schedule for retyping from scratch my revision of Blood Trip in 2022. You were the one to suggest that grueling process. I do think it pays off. Sticking with the subject of editing, I recall with fondness most of our virtual “writer meetings” at the online version of The Last Estate and feeling like it was a collaborative effort, and I didn’t really feel comfortable with my article going forward to publication until others, in particular William Duryea, signed off on the piece. I think there is a price to be paid for having a “go it alone” mindset sometimes. What is next for Beyond the Last Estate, the magazine?

I miss William’s influence so much. I wish he would come back around. As far as BtLE, I’m hoping to have issue 4 out by August with a cover story on John Tottenham. I hope to have the old Last Estate archives back up online with Rudy Johnson’s help too. I made the decision to go from quarterly to triannual so I can still work on my own stuff. I promised myself I’d finish the rough draft of my next novel by the end of the year, so here’s hoping.

///Buy Gabriel Hart’s novel and other Pig Roast Publishing books here, support the underground

COMING SOON TO CHLOROPHYLL & HEMOGLOBIN:

David Kuhnlein’s top five poetry books

Sketchy music reviews: I listen to harsh noise tapes bought from PUKE PINK website

Probably more strange writing about sike-ological objekts