NOISE ROCK MEMORY-EXCAVATION

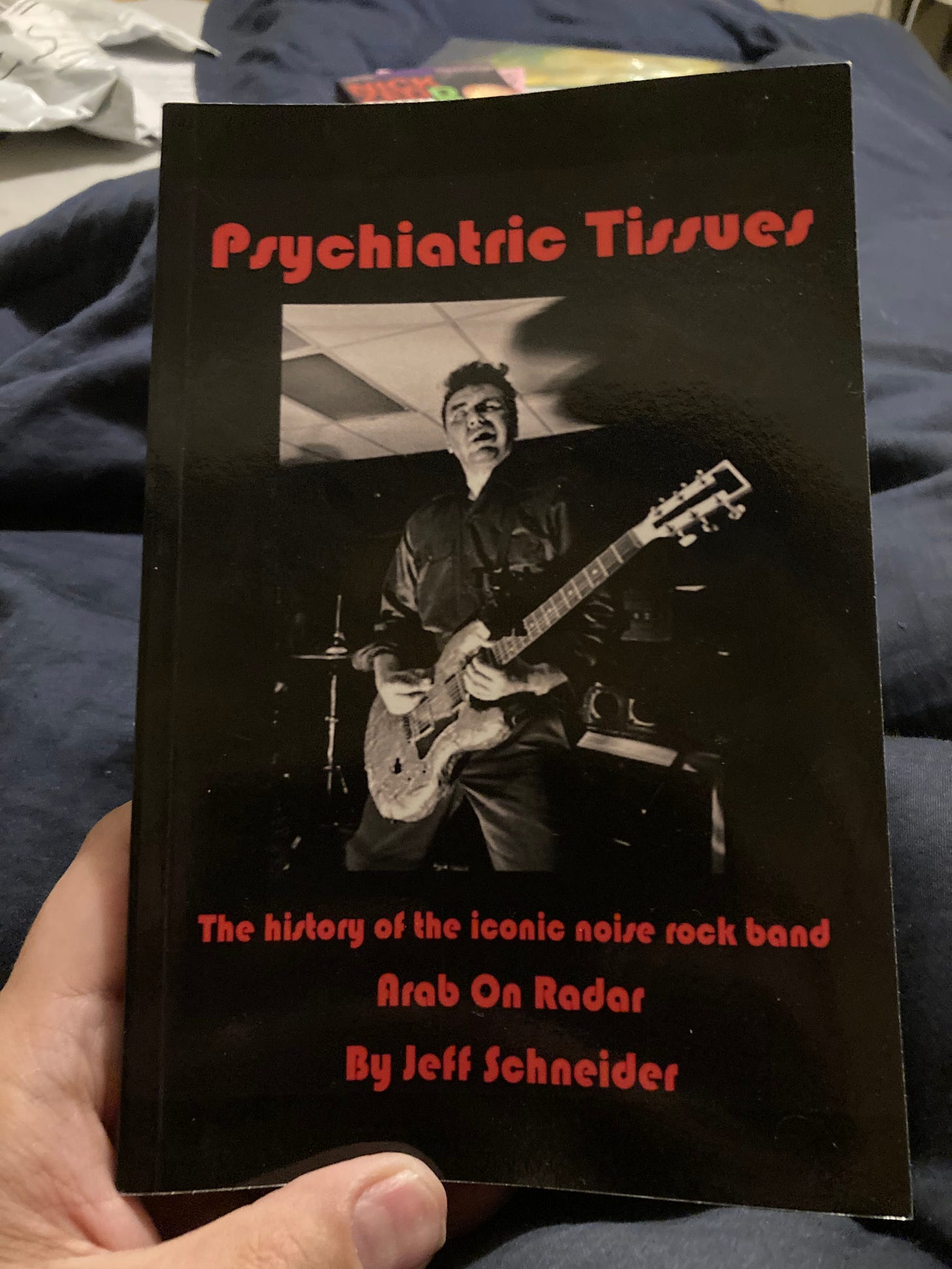

Psychiatric Tissues. Jeff Schneider. Pig Roast Publishing, 2018. 269 pages.

“I wanted to punch Neutral Milk Hotel in the face, not the people in the band, but the songs that represented them.” —Jeff Schneider, Psychiatric Tissues

Musical memoir is a genre I don’t have much familiarity with. Neither did I know much about the iconic noise rock band Arab On Radar before I read the book Psychiatric Tissues by Jeff Schneider. But this didn’t matter because I easily read the book in two days and was thoroughly engrossed. Schneider was a guitarist in the band who went by the nom de guerre Mr. Clinical Depression (virtually all the band members had such monikers), and his ability to tell a story—replete with grisly anecdotes from the road, analyses of the indie music industry in the 90s and 2000s, shoutouts to individuals along the way who either gave their all to help the band or were obnoxious hindrances, proud reflections on the band’s gritty hometown of Providence RI—is remarkable and assured. It’s rough and bears the traces of long experience and knowledge whereof he speaks.

It’s also funny as fuck and had me laughing out loud, real uncontrolled laughter which doesn’t hardly ever happen when I’m reading books, even books that are considered to be conventionally humorous. It takes something special and hard to define to make me lose it. This book has that thing and it’s just one of Schneider’s talents that helps pull you like a hooked fish steadily through the book. His sense of humor derives from the working class wise guy voice of an artist from the East Coast crossing paths with the freaks, pretentious “sweater-lovers,” people with identical “Romulan” haircuts, shysty music industry types, cookie-cutter hardcore bands, and other denizens of the often compromised post-Nirvana indie music scene as it existed in those years. Arab On Radar toured the USA and Europe, collecting bizarre, sometimes violent experiences, and one area in which the book excels is Schneider’s ability to quickly paint witty pictures of the people the band meets, and also, of course, the people the band is comprised of. The encounter in the UK with ineffectual bobbies (“goofy ass cops with yellow construction bibs”) while looking for stolen musical gear was just one of many hilarious portraits too numerous to recount, but he does.

The book is many things but one of its more utilitarian functions is to serve as a handbook for musicologists who want to delve into a musical subculture as it has existed around the turn of the millennium and beyond. The arcane lore is given—of bands, labels, producers, studios, and perhaps one of the most fascinating bodies of information in the book is an almost night-by-night recounting of the venues Arab On Radar played at in cities around the country and world. The band was apparently phenomenal in their live performances, and to this chump reader, who hasn’t seen live music since the 90s, I was absorbed in the tales of humping gear in and out of locales, playing with maximum devotion even when there was “no one” in the audience, getting in scuffles both social and physical with other bands (Death Cab for Cutie mistaking AOR for roadies who will handle their gear like servile coolies was priceless), and just the memory-excavated physical descriptions of the stages and performance spaces, especially when the skepticism of Schneider and the rest of the band seemed to give way to awed approval.

Violence, sex, and drugs color much of the story; it is a blessing that Schneider can remember the details as well as he can, but again, he does. The book isn’t all raucous adolescent fun, of course. Often a gnawing anxiety and depression attacks the author, and the regret over lost friendships, lost opportunities for love, and just people vanished to time, unavoidable to those writing a memoir about their youth, take their toll. The passages offering bitter criticism of the fake weakness and elitism of musical scenes strike a familiar chord to those of us who came of age in the 90s when the issue of bands selling out and being fake were common currency (I’m sure it’s a perennial problem, but Schneider’s tale had a generational resonance for me somehow).

All that’s left to do now is to pay attention to the catalog of music that existed, and do the archaeology that this book gives a series of guideposts for.

enjoyed reading this review