A DIFFERENT TYPE OF ADULT

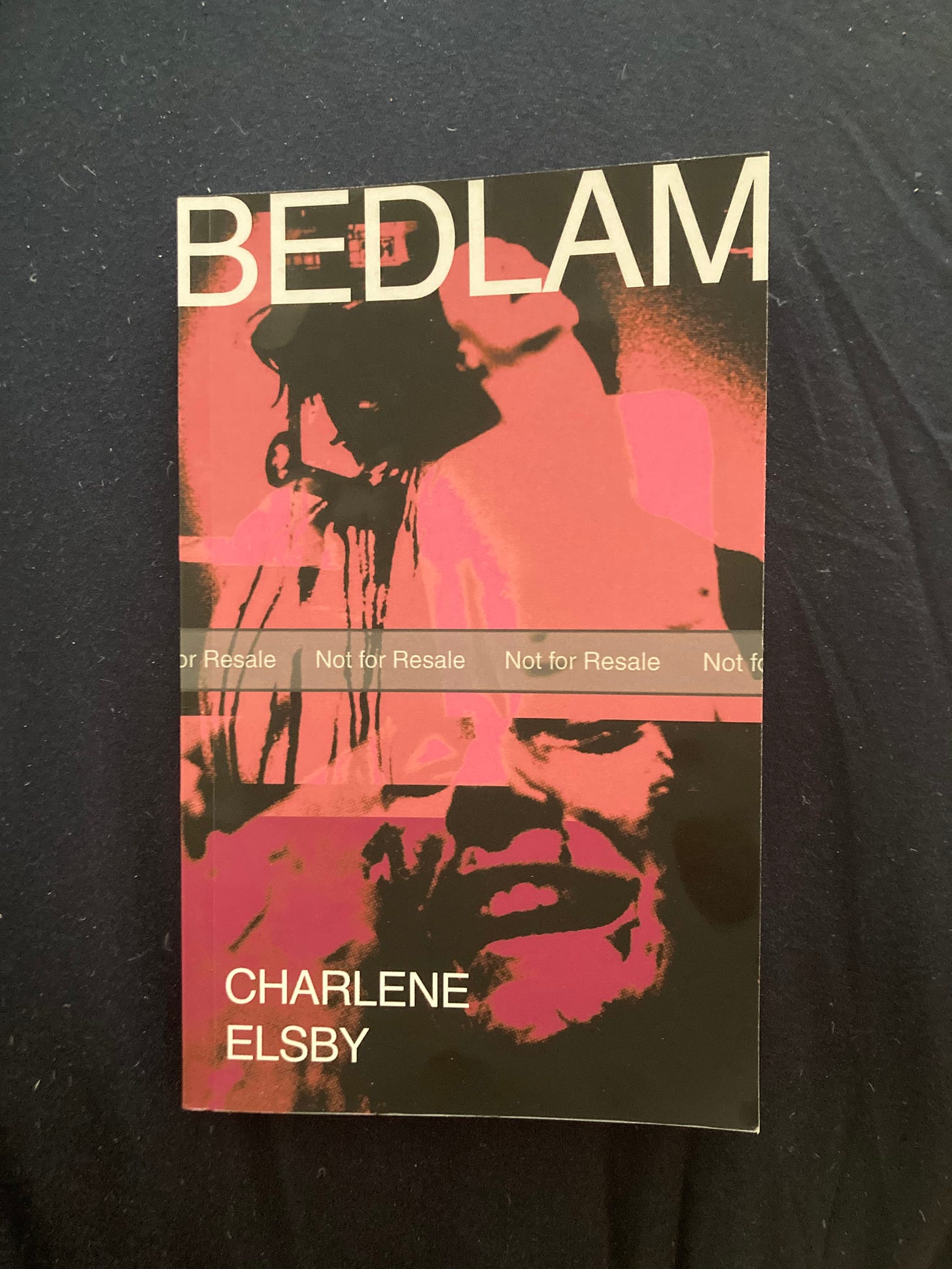

Bedlam. Charlene Elsby. Apocalypse Party, 2023. 131 pages.

I’m always fascinated with the ways that concepts such as genre can be perturbed and subverted. Genre fiction needs to have certain characteristics to make it easier to group with other fiction, easier to sort. It’s kind of an unavoidable laziness or path of least resistance to say that all horror fiction should be scary or should deal with supernatural themes or have similar “grouping tendencies” so that prospective buyers can know what they’re in for should they put their money down when getting a book.

Book reviewers are part of this machinery, to pretty much everybody’s displeasure. If I were to tell you that Charlene Elsby’s short story collection Bedlam was “psychological horror,” it wouldn’t really be adequately doing the descriptive job and would leave crucial information unexplained. The sites of action in these fourteen stories are locked firmly into the hermetic company of first-person narrators (as far as I could tell) whose goals seem to be in unearthing aspects of human psychology that are, to put it mildly, horrifying. Horripilating could be another term, defined as undergoing “horripilation” in which the hairs stand erect from the body due to cold, fear, or excitement. These are not calming stories. Neither are they in particular stories where a formal payoff is given that might mark them as “genre fiction.” The payoff is not narrative but the sort of thing you get from peering into a box at something you really shouldn’t want to get an eyeful of.

Right away I want to give the disclaimer that I am not fluent enough in the lingo of philosophy to talk about some underlying features of Elsby’s fiction here. I have gathered elsewhere that she has a doctorate in philosophy and has been a philosophy professor at times. Some of the narration in the stories bears the traces of this kind of argumentation and mental flow. I’ll bet you that if you were up on your philosophical terminology and schools of thought the stories might mean something special to you in this regard. As it was, with me, the stories were like the chattering products of a powerful mind that cannot rest, cannot come to a kind of peaceful end point. I don’t need to know philosophy to take insight and enjoyment from Elsby’s reports from a unique, sometimes darkly humorous, and often harrowing place on what life means. Elsby’s narrators, those inescapable women (they always seemed to be clearly female to me), are of a different type of adult than you, more psychologically alien and yet wearing the face — surface — of the person on the other side of the boardroom table in your workplace, dancing at the bar, getting her hair cut at the salon. This other type of adult observes things from a bleak, fearful vantage point. The fiction seems to be a kind of warning that if you were to finally be able to peer into the thoughts of the people around you, driving in traffic, waiting in line at the supermarket, etc, you would be blown away by the frightening noise you would discover there.

But, and this is a crucial point, Elsby’s speakers are not necessarily others. There’s enough in common with you that it’s not science fiction, these aren’t true aliens. We all have romantic disappointments that leave us wounded and trying to establish what exactly happened, how much the problems originated within us (see “Another Man’s Bruises,” “Bad For The Baby,” other stories). The typical dating profiles of the narrators in Elsby’s stories would be a set of terrifying documents, but it’s nothing we aren’t familiar with in certain generic ways from our own lives. Elsby, like a tour guide leading timid civilians on a social safari, just as easily transgresses into anti socially violent places. Going out of your typical drive to hit a midnight jogger seems like a rational decision. Sending an offensive picture to the wrong lady on the wrong day could result in your damn near human sacrifice; in “Split Dick David Does a Dick Pic on a Tuesday” we see the terrifying but all-too orderly logic of female vengeance enacted against the photographed phallus of a man, who will mistakenly try to argue his way out of being targeted for such stomach-turning, gory retribution since other men have taken actions just as bad:

“Because of his limited experience, he doesn’t know what it’s like to take on the characteristics of a set. Of course, the women are all quite experienced in this. We have to pay for what some other woman has done. More likely, we have to pay for what all women are perceived to have done. In actuality, we’re all paying for everything that every other woman has done to some man, because he can’t differentiate between us well enough to figure out that I’m neither his ex-girlfriend nor his mom…The point is, the I’m not the worst man to live argument isn’t going to work with me, because here in reality we embody the universals in which we participate, and while you can not all men me all you like, you have to recognize that some men is enough, and that what matters now is that you’re the man in imminent danger, because I have decided that’s how it’s going to be.”

Reading the collection Bedlam in one sitting means that the discomfort level will not let up, but because there are fourteen stories, discomfort will take on one of fourteen more or less distinct angles, and it’s a kaleidoscope of fear loaded with fourteen different bits of darkly colored glass tumbling into different configurations. One story “So Many of Them,” a childhood reminiscence of owning an aquarium full of multiplying mice, was particularly skin-crawling which is no small statement given the rest of the book’s offerings.

Bedlam is a volume for readers daring to eavesdrop on one of the most unsettling voices in indie lit as it verbally marks out the dimensions of its inescapable existential cage — perhaps to commiserate? is there hope enough for that? are we locked in too? There’s value in plumbing the depths and measuring the dark unexplored recesses of the mind, and that’s the often unpleasant task we turn to writers to do. I don’t know if it’s a sign of our times, of our nation, of how nervous systems diverge, what is the explanation, but a writer like Elsby could, with her descriptive powers, conceivably help the rest of us by providing us with illustrations of what she sees as she gazes down from an arrow slit onto the landscape of consciousness’s futility.

This review is great and the reason I subscribed to your newsletter!

Wonderful review, Jesse!